Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

The demographics of the exposure to dangerous environmental conditions have had a lot to do with economic behaviours and ethnic backgrounds of the residents of major cities in recent times. Such racial prejudices are extremely common in cities within America where white families often move out of neighbourhoods with majority of black/hispanic communities. This of course motivates a culture of segregation – but this isn’t something recent. Such segregation was a by-product of housing policies that made it extremely hard for ethnic minorities to live in privileged/white neighbourhoods. Home-owners associations added extra costs for blacks or other racial minorities if they were to buy a home in privileged white neighbourhoods. These ‘white’ neighbourhoods came with environmental conveniences (like parks, massive plantation projects, less pollution) reinforcing racial discourses through the environment. The ‘white flight’ also caused unequal processes of urban development allowing the exploitation of unequal division of landscapes. Hence, the exposure of nonwhites (and their neighbourhoods) to social, ecological and health implications of environmental hazards has become extremely common.

Disproportionate siting of industries near these impoverished communities normalizes the placement of hazardous facilities in residential areas that host ethnic/racial minorities. Cleanup of these waste sites coupled with the unavailability of any environmental amenities puts these communities into situations of extreme vulnerability putting these residents at a higher risk of health hazards for instance breathing problems, constant explosions and cancer clusters. This then leaves open space for various forms of environmental injustices. The release of air toxins are often also commonly associated with working class minority neighbourhoods. In fact, a planning document recorded the following within a working class/non-white community in the city of Los Angeles , “small, older, single family homes situated between or adjacent to large commercial and industrial buildings. . . . The noise, dirt, heavy truck and trailer traffic along industrial/residential edges also severely detracts from the quality of life of nearby residents. Views from homes to loading docks, auto wrecking and repair yards, and heavy machinery do not provide the amenities traditionally associated with residential life” (Garrow et al. 1987:54).

Environmental racism is becoming clear with projects being deliberately introduced near certain neighbourhoods. For example, “In Atlanta, 82.8% of blacks live in waste-site areas, compared to 60.2% of whites. Similarly, in Los Angeles, 60% of Hispanics live in waste-site areas, compared to 35.3% of whites.” (Bullard,2000) An increasing number of people of colour have been found living near the coal fired power plants in America – the transportation and housing facilities have seen major discounts in these areas and as a result racial inequalities have exacerbated more than ever. Often more than not, these neighbourhoods are called the ‘sacrifice zones’ of the city because these low income minority/non-white neighbourhoods get hit the hardest with severe floods, weather events and droughts. The normalization of systemic racism through discriminatory policies has meant these non-white neighbourhoods are exposed to ecologically destructive mega projects that directly challenges the human rights in many cases as mentioned: “Environmental degradation in places where Indigenous populations and socioeconomically and politically disadvantaged people of all races live is “always linked to questions of social justice, equity, rights and people’s quality of life in its widest sense” (Agyeman, Bullard, and Evans 2003, 1).”

Examples of such extreme forms of racial inequalities include the Cancer Alley in Louisiana, water crisis in Flint-Michigan, sugar industry pollution in Florida and toxic coal ash in Alabama. Hazardous waste contamination from these sites make nearby low income/people of colour communities extremely vulnerable to climate change. In fact the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice has reported the highest number of toxic waste facilities near minority communities. According to them there was a consistent national pattern where, “race is the most significant determinant of the location of hazardous waste facilities.” (Godsil,1991)

The lack of environmental protection law or their reinforcement in these low income neighbourhoods results in a higher number of environmental violations experienced. Unsound housing, schools with asbestos problems, playgrounds with lead paint, contaminated facilities ,airports near residences, landfill and chemical plants are huge determinants of environmental racism in these low-income non white areas. Many children in these areas tend to grow up with mercury poisoning causing them to perform relatively poorly in schools and beyond. Even the soil, playground ditches and gardens contained high levels of arsenic in many of these areas according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Jammed roadways resulting in increased production of exhaust fumes, views of cranes and constructions are also ceaseless sites for these neighbourhoods. Industrial dumping causes the contamination of even fresh water producing multi coloured streaks in the water causing extreme health risks. Coupled with the prior is the depletion of animal habitats due to low oxygen levels and scarce nutrition sources. Environmental disparities result in the unequal share of social factors like employment, safety, housing etc.

Following are case studies of five cities that showcase major environmental inequalities:

Houston, Texas: Northwood Manor Neighborhood: With above 80% of black population, a whispering pine landfill was built within the area of a high school exposing the students to major health hazards.

West Dallas, Texas: With more than 85% black population, a lead smelter was installed near the residential area that pumped more than 269 tonnes of lead into the air every air.

Institute, West Virginia: With over 90% of its population black, a union carbide chemical plant was installed near the state college and rehabilitation centre.

Alsen, Louisiana: With over 95% of its population black, a commercial waste site has developed with serious health and odour issues within the area.

Emelle-Sumter County, Alabama: With almost 70% of its population non white, the area has become the host of the nation’s largest hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facility. This has especially contaminated the water within the area posing health hazards to the residents.

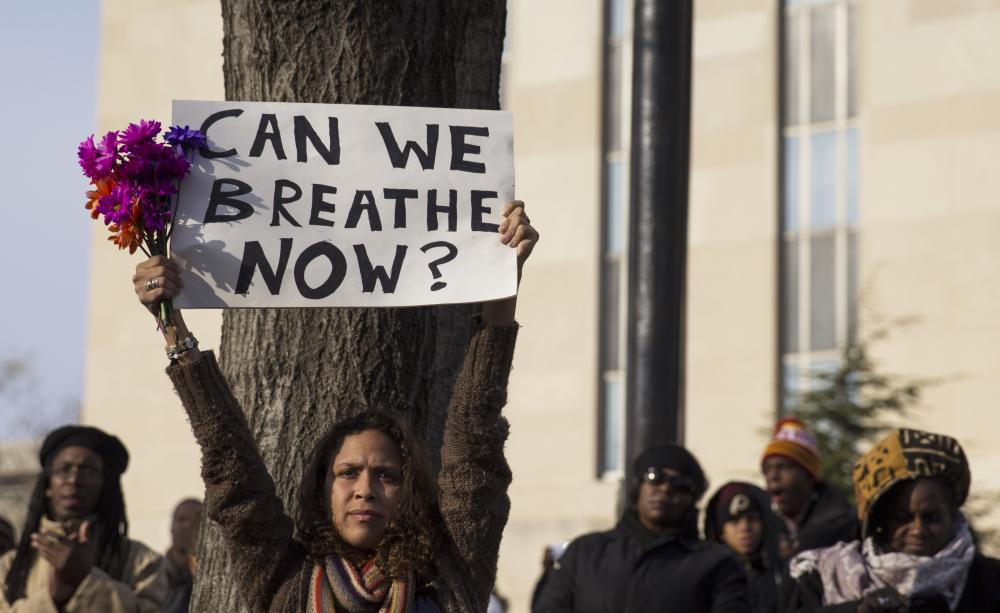

Environmental justice movements have sprung up like the Chicano women in Los Angeles who have spoken up against the unequal distribution of waste facilities within the city or native Alaskans who have spoken up about the radio-active waste that was dumped in low income neighbourhoods. Much of this environmental racism is also a result of political agendas and the lack of ethics in the capitalist, corporate structures that tend to keep their growth as their priority while jeopardizing with the environment. Environmental activists taking up the forefront of policy-making agendas has given some hope against years of racial discourses. Many environmental justice plans have sprung up as a result. It is evident since, “more than $12 million in grants for local community projects serving environmental justice areas, and allocated resources to address health inequities, air quality, and renewable and efficient energy.” (Javorsky,2019) Under Trump’s leadership however, environmental justice movements have seen a major downfall due to the president’s lack of belief in environmental hazards or climate change let alone environmental injustices due to racial discourses. However, according to Bullard neighbourhoods in these cities face environmental racism also because many privileged find these areas as ‘paths of least resistance.’ Due to low number of advocates or lobbyists speaking up against racial prejudices – it gets easier for the white privileged man to exploit them. Bullard claims that “local governments and big businesses take advantage of people who are politically and economically powerless, and set-up shop in places where there is lax enforcement of environmental regulations.” (Bullard, 2000)

It is clear then that the topic of environmental racism is becoming fuzzy by the day and in fact a shortfall of proper strategy has caused institutional barriers to environmental equality/justice. It is only, in this age of technology, now possible to achieve justice through the communities own struggle to keep up and creating networks so as to share information and form an organized opposition against political, historical and even social (racist) jurisdictions.

WORKS CITED

Bullard, Robert D. 2000. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. 3rd Edition. Westview Press.

Checker, M. (2005). Polluted promises: Environmental racism and the search for justice in a southern town. New York: New York University Press.

Bullard, R. D. (1993). Confronting environmental racism: Voices from the grassroots. Boston: South End Press.

Javorsky, N. (2019, May 12). Which cities have concrete strategies for environmental justice? Retrieved from https://grist.org/article/which-cities-have-concrete-strategies-for-environmental-justice/

Environmental Injustice: Is Race or Income a Better Predictor? Social Science Quarterly , December 1998, Vol. 79, No. 4 (December 1998), pp. 766-778

Godsil, R. D. (1991). Remedying Environmental Racism. Michigan Law Review, 90(2), 394. doi:10.2307/1289559

ADDRESSING ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM: Robert Bullard: Journal of International Affairs , Vol. 73, No. 1, CLIMATE DISRUPTION (Fall 2019/Winter 2020), pp. 237-242

Robyn, L. M. (2020). Environmental Racism:. Indigenous Environmental Justice, 92-114. doi:10.2307/j.ctv10qqwrm.9

Pulido, L. (2017). Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California. Environment, 379-407. doi:10.4324/9781315256351-17

With increasing urbanization and development in cities such as Faisalabad – social and individual identities are rapidly changing. However, the idea of gendered division within cities especially in development thinking has always put certain populations at a disadvantaged position compared to the others. Apart from huge differences in infant mortality, literacy and malnutrition cases between different genders, gendered segregation is often visible in specific demarcations of geographical spaces within the city of Faisalabad. The belief that any gender other than the cis-gender-male belongs to the boundaries of their houses (char-deewari) has reinforced the division of public and even private spaces in favour of the already male-dominant and patriarchal community within the city. Faisalabad’s transgender communities in particular face extreme forms of gendered demarcations and are a direct victim of urban informality and urban violence.

Urban Informality

Transgender persons have been greatly secluded to what many locals call the ‘Khusra Gali (khusra being a term commonly used for the third gender and gali implying street).’ The housing, sanitation and hygiene conditions remain archaic compared to the city’s other posh areas like Abdullah town that have seen rapid urbanization in recent years. Even though, Pakistan as a state has often tried to introduce regulations in the favour of the community to go in coherence with Foucault’s argument “that the modern discourse on sexuality gradually emerged in mainstream Western societies through the technologies of power and bodily discipline,” Pakistani society’s uneasy coexistence with the trans-gender community has almost always been quite apparent. Insecure and secluded living spaces restrict their mobility, economic and educational opportunities to a huge extent. These secluded residential spaces for the transgender community often don’t offer basic education and medical centres while the others in the city refuse to enrol the third gender. These trans-genders usually live in katchay (mud) houses built on un-even roads and exposed water pipelines. There are zero to minimum waste disposal provisions exposing the residents to health risks every hour of the day. Police officers often invade the residential areas of these trans-genders by raiding their houses and different spaces without any legal notices due to inadequate security restrictions by local government or authorities. Mobility remains a huge issue too since many local car services often refuse to come to areas where trans-genders reside (for eg Khusra Gali) and public transport provisions remain far from the areas where they reside. In case transgenders do use the public transport for mobility – they face all kinds of harrasments and catcalling has almost been normalized. The recent rapid urbanization has in fact had a de-politicizing affect in the city that has created power rivalries and the idea of competing interests just as Morgenthau suggests that the desire of power “manifests itself as the desire to maintain the range of one’s own person with regard to others, to increase it, or to demonstrate it.” (Troy,2018)

Keeping this certain conceptualization of power in mind, it is quite clear that only one group maintains power as opposed to the other – hence the birth of an essential characteristic of the power-politics in the domain of recently urbanized cities. In the case of Faisalabad, it can be applied to the power-politics played between normative (stronger) genders/gender roles versus the trans-gender community – the khwaja-siras. Rene Girards memetic theory also suggests that human conduct is all about the imitation of desire (to power) and hence leads to the formation of the ‘global street’ that is powerless human agglomerations in the urban sphere exactly against the powerful human communities.

In fact, this exclusion leads to extreme situations of vulnerability among the transgender communities and often inculcates within them, internalized humiliation. The community then also appears to adopt a rather invisible approach in which they remain socially passive within the city that is keep their areas of residence secluded and low-key. This goes in coherence with Bayat’s (2004) ‘quite encroachment’ according to which “practice and/or change is subtle and hidden rather than radical and public, or because certain groups lack the resources to mobilise” (Banks,2019)

This passive participation furthers the inferiority of khwa-siras within the city and also obscuring the ‘backwardness’ that exists within the otherwise apparent urbanization in terms of safety, hygiene, infrastructural development, general lack of opportunity and resources and disorder.

Urban Violence

Often, due to limitations in job opportunities, trans-genders, also commonly known as khwaja-siras in the cityare forced to work as prostitutes and are often subjected to abuse and violence. It is extremely common for men to have mehfils (gatherings) where transgender persons are invited to dance for hours until those men throw hefty amounts of cash to demonstrate their superiority and wealth. Such practices are also extremely common at weddings and other celebrations within the city. The practice has been so deep-rooted within the culture of the city that often, having no other choices for income, these transgender persons themselves show up at events and dance on the streets until some donation or reward is given to them. However, it is also extremely common for these trans-gender persons to be harassed at events and rape cases are extremely common. In case of consensual sex-work, these transgender persons are often forced to have sex with several men at the same time even though they had only agreed to one. In fact, khwaja-siras are, many times raped in their very own homes due to lack of secure infrastructural facilities within the spaces they reside. According to The Express Tribune, two women named Saima and Asma were raped inside their house in Jaranwala Road, Faisalabad upon refusal to have sex earlier. (Islam, 2016) However, the police themselves remain extremely insensitive to the community and often refuse to file any harassment cases for these trans-women/men and in fact remain light-bearers of these meta-narratives against trans-genders themselves. Usually, transgender individuals who are victims of harassment and rape just accept the abuse and ignore their psychological trauma due to the banal meta-narratives that surround much of the city’s circumference. In fact, the culture of morality in the city still goes hand in hand with the idea of ‘forcing corrective behaviour ’ and hence the transgender persons are often beaten up and hurled stones at for being what the locals call, under the influence of religious motives, deviant and un-Islamic. This has led to a great deal of Gender Identity Disorders within the particular marginalized community in Faisalabad. Added to this is the entire idea of gurus and chelas that forms a nexus of a toxic yet never ending power-sharing culture that reduces the values of these transgender persons down to either being ‘economically active’ or being ‘sustainable enough.’ This causes an infliction of beauty standards that need to be fulfilled by all the chelas for his/her guru to be able to economically make their space within the khwaja-sira community. Often, transgender persons see their hair as a sign of beauty – something that gets them work. A very common form of abuse in the city hence is men raping and then shaving the heads off of these transgender persons to ‘de-beautify’ them.

Even though, efforts are on way to uplift the position of the community within the city – it really is the traditional meta-narrative that despite all efforts secludes the transgender community in the city and puts them at the forefront of all inequalities socially, economically and politically.

Bibliography

Tribune.com.pk. (2016, July 29). Two trans-women raped in their home in Faisalabad. Retrieved from https://tribune.com.pk/story/1150578/heinous-crime-two-trans-women-manhandled-raped/?

Troy, J. (2017). The Power of the Political in an Urbanizing International. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3034363

Divan, V., Cortez, C., Smelyanskaya, M., & Keatley, J. (2016). Transgender social inclusion and equality: a pivotal path to development. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 19(3 (Suppl 2). doi: 10.7448/ias.19.3.20803

Roy, A., & AlSayyad, N. (2004). Urban informality: transnational perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia. Lanham (Md.): Lexington Books.

Adeel, M., & Yeh, A. G. O. (2018). Gendered immobility: influence of social roles and local context on mobility decisions in Pakistan. Transportation Planning and Technology, 41(6), 660–678. doi: 10.1080/03081060.2018.1488932

Quite imprecisely, the discrimination against one or more groups within a community due to the recent development and systemization of generating and distributing wealth – especially and particularly the disproportionate demarcation of groups into the ideal and the non-ideal, the needed and the problematic that allows certain groups to have ‘systematic power’ (Stone, 1980) over the others is generally referred to as inequality. The construction of such inequalities has becomes visibly clearer in cities with the intensification of city programs that fancy and cater to certain elite strata and social groups that conduct themselves as the representatives of social and urban progress. Identities are often ascribed to these groups that enhance the formation of a rather urbanized idea of a city both culturally and economically. These inequalities comprise of differences in incomes, infrastructural facilities, security/law and order, education and health facilities and land availability. With an increase in population, a growing resurgence in the idea of globalization and capitalism within urban cities has allowed the gaps between groups to further widen thereby reorganizing hierarchies on a whole new level. Unequal access to land, water and sanitation services, health services, unequal employment opportunities and education facilities and otherwise overcrowded and unpleasant environments based on class, religious and cultural differences clearly portray the dynamics within which inequality works in cities. The reinforcement of privilege that is illustrated in inadequate provision of facilities to low income groups that remain overcrowded in one part of the city thereby resulting in extreme cases of unhygienic environments and over-pollution just alongside wealthy settlements that usually remain gated and under-crowded latching onto unsustainable resources such as personal swimming pools etc are a clear depiction of vast inequalities within the cities. These secluded spaces with exclusive facilities have different social meanings – security to the ones living inside and ‘keep out’ or ‘not allowed’ to the ones living outside. McKenzie calls these gated communities as ‘Planned Unit Developments’ or ‘Common Interest Developments.’ On the other hand, the poverty stricken areas of the city are often called ‘areas of darkness and hopelessness’ or ‘areas of social disorganisation and political inaction.’

The city of Faisalabad parodies major urban inequalities, especially quite recently where the arousal of newer settlements like Canal Road and Koh-i-Noor Nagar against older settlements Satyana Road and Ghulam MuhammadAbaad have caused major disruptions in the map of the city. Newer shopping complexes, video camera surveillance and other sophisticated security systems are sprouting up in secluded residential areas where privacy and safety has also become a commodity that is only affordable to the upper strata of the society. Gendered and religious inequalities cause and take up major spaces in the city of Faisalabad as well where huge populations of Christians find themselves in over-crowded colonies facing harsh situations and scarce facilities. A large population of trans-genders find themselves as residents of the city who are yet again – secluded to particular lumps within the city trying to make ends meet by performing mujras at weddings and other occasions. Hence, not only economical but also social factors cause clear demarcations within the city and can clearly be seen having an effect. Having had the chance to attend several occasions in the city of Faisalabad, I could personally feel the differences in the public spaces involved that created extreme socio-demographic profiles where the elite had to themselves air conditioned restaurants, cafes and multiplexes – the not so well-to-do had katchay (houses made of mud) houses, broken roads, scarce to no educational and health facilities and streams of untreated, unhygienic water running throughout the neighbourhoods that brought risks numerous health conditions and mortality rates only increased. It is however, not surprising as S Akbar Zaidi – a Karachi based political economist says, “With the rich getting richer, and the middle class expanding, with political control in the hands of both under the despotism of capital in the neoliberal present, inequality is only going to grow in Pakistan.” (Zaidi, DAWN 2017)

In fact, government policies now tend to focus more towards developmental approaches with compartmentalized interventions and target-group approaches thereby resources being allocated for the benefit of one group. However, it isn’t just plainly government policies that are to be blamed. Larger cities have higher variations in skill thereby having large differences in monetary benefit. This can clearly be summed up as, “Large cities also attract rich households because they reward their skills more highly than smaller cities – a “superstar effect” in “superstar cities” (Behrens et al. 2014, Gyourko et al. 2013, Rosen 1981).” Hence, larger cities provide incentives to the one’s with proper amount of skill – however the idea of failure (in the attainment or application of those skills) associated causes disproportion and inequality. As exploitative as it sounds, increasing globalization and capitalism has caused local markets in these urbanized cities to the reward the skilled that directly translates into deprivation for those who are unskilled. In such cases, increased participatory democracy might be able to address issues of inequality and regulate the provision of proportionate resources by combating the bourgeois ideology.

BIBLIOGRPAHY

Zaidi, S. A. (2018, October 1). Inequality, not poverty. Retrieved February 2, 2020, from https://www.dawn.com/news/1310296

Inequality in big cities. Retrieved February 2, 2020, from https://voxeu.org/article/inequality-big-cities

This is an example post, originally published as part of Blogging University. Enroll in one of our ten programs, and start your blog right.

You’re going to publish a post today. Don’t worry about how your blog looks. Don’t worry if you haven’t given it a name yet, or you’re feeling overwhelmed. Just click the “New Post” button, and tell us why you’re here.

Why do this?

The post can be short or long, a personal intro to your life or a bloggy mission statement, a manifesto for the future or a simple outline of your the types of things you hope to publish.

To help you get started, here are a few questions:

You’re not locked into any of this; one of the wonderful things about blogs is how they constantly evolve as we learn, grow, and interact with one another — but it’s good to know where and why you started, and articulating your goals may just give you a few other post ideas.

Can’t think how to get started? Just write the first thing that pops into your head. Anne Lamott, author of a book on writing we love, says that you need to give yourself permission to write a “crappy first draft”. Anne makes a great point — just start writing, and worry about editing it later.

When you’re ready to publish, give your post three to five tags that describe your blog’s focus — writing, photography, fiction, parenting, food, cars, movies, sports, whatever. These tags will help others who care about your topics find you in the Reader. Make sure one of the tags is “zerotohero,” so other new bloggers can find you, too.