The demographics of the exposure to dangerous environmental conditions have had a lot to do with economic behaviours and ethnic backgrounds of the residents of major cities in recent times. Such racial prejudices are extremely common in cities within America where white families often move out of neighbourhoods with majority of black/hispanic communities. This of course motivates a culture of segregation – but this isn’t something recent. Such segregation was a by-product of housing policies that made it extremely hard for ethnic minorities to live in privileged/white neighbourhoods. Home-owners associations added extra costs for blacks or other racial minorities if they were to buy a home in privileged white neighbourhoods. These ‘white’ neighbourhoods came with environmental conveniences (like parks, massive plantation projects, less pollution) reinforcing racial discourses through the environment. The ‘white flight’ also caused unequal processes of urban development allowing the exploitation of unequal division of landscapes. Hence, the exposure of nonwhites (and their neighbourhoods) to social, ecological and health implications of environmental hazards has become extremely common.

Disproportionate siting of industries near these impoverished communities normalizes the placement of hazardous facilities in residential areas that host ethnic/racial minorities. Cleanup of these waste sites coupled with the unavailability of any environmental amenities puts these communities into situations of extreme vulnerability putting these residents at a higher risk of health hazards for instance breathing problems, constant explosions and cancer clusters. This then leaves open space for various forms of environmental injustices. The release of air toxins are often also commonly associated with working class minority neighbourhoods. In fact, a planning document recorded the following within a working class/non-white community in the city of Los Angeles , “small, older, single family homes situated between or adjacent to large commercial and industrial buildings. . . . The noise, dirt, heavy truck and trailer traffic along industrial/residential edges also severely detracts from the quality of life of nearby residents. Views from homes to loading docks, auto wrecking and repair yards, and heavy machinery do not provide the amenities traditionally associated with residential life” (Garrow et al. 1987:54).

Environmental racism is becoming clear with projects being deliberately introduced near certain neighbourhoods. For example, “In Atlanta, 82.8% of blacks live in waste-site areas, compared to 60.2% of whites. Similarly, in Los Angeles, 60% of Hispanics live in waste-site areas, compared to 35.3% of whites.” (Bullard,2000) An increasing number of people of colour have been found living near the coal fired power plants in America – the transportation and housing facilities have seen major discounts in these areas and as a result racial inequalities have exacerbated more than ever. Often more than not, these neighbourhoods are called the ‘sacrifice zones’ of the city because these low income minority/non-white neighbourhoods get hit the hardest with severe floods, weather events and droughts. The normalization of systemic racism through discriminatory policies has meant these non-white neighbourhoods are exposed to ecologically destructive mega projects that directly challenges the human rights in many cases as mentioned: “Environmental degradation in places where Indigenous populations and socioeconomically and politically disadvantaged people of all races live is “always linked to questions of social justice, equity, rights and people’s quality of life in its widest sense” (Agyeman, Bullard, and Evans 2003, 1).”

Examples of such extreme forms of racial inequalities include the Cancer Alley in Louisiana, water crisis in Flint-Michigan, sugar industry pollution in Florida and toxic coal ash in Alabama. Hazardous waste contamination from these sites make nearby low income/people of colour communities extremely vulnerable to climate change. In fact the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice has reported the highest number of toxic waste facilities near minority communities. According to them there was a consistent national pattern where, “race is the most significant determinant of the location of hazardous waste facilities.” (Godsil,1991)

The lack of environmental protection law or their reinforcement in these low income neighbourhoods results in a higher number of environmental violations experienced. Unsound housing, schools with asbestos problems, playgrounds with lead paint, contaminated facilities ,airports near residences, landfill and chemical plants are huge determinants of environmental racism in these low-income non white areas. Many children in these areas tend to grow up with mercury poisoning causing them to perform relatively poorly in schools and beyond. Even the soil, playground ditches and gardens contained high levels of arsenic in many of these areas according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Jammed roadways resulting in increased production of exhaust fumes, views of cranes and constructions are also ceaseless sites for these neighbourhoods. Industrial dumping causes the contamination of even fresh water producing multi coloured streaks in the water causing extreme health risks. Coupled with the prior is the depletion of animal habitats due to low oxygen levels and scarce nutrition sources. Environmental disparities result in the unequal share of social factors like employment, safety, housing etc.

Following are case studies of five cities that showcase major environmental inequalities:

Houston, Texas: Northwood Manor Neighborhood: With above 80% of black population, a whispering pine landfill was built within the area of a high school exposing the students to major health hazards.

West Dallas, Texas: With more than 85% black population, a lead smelter was installed near the residential area that pumped more than 269 tonnes of lead into the air every air.

Institute, West Virginia: With over 90% of its population black, a union carbide chemical plant was installed near the state college and rehabilitation centre.

Alsen, Louisiana: With over 95% of its population black, a commercial waste site has developed with serious health and odour issues within the area.

Emelle-Sumter County, Alabama: With almost 70% of its population non white, the area has become the host of the nation’s largest hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facility. This has especially contaminated the water within the area posing health hazards to the residents.

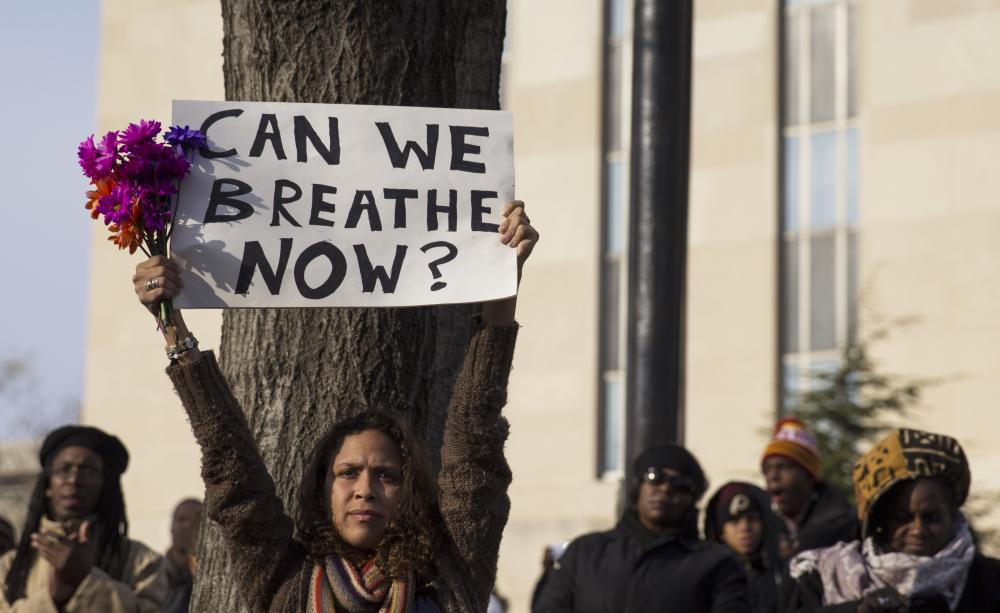

Environmental justice movements have sprung up like the Chicano women in Los Angeles who have spoken up against the unequal distribution of waste facilities within the city or native Alaskans who have spoken up about the radio-active waste that was dumped in low income neighbourhoods. Much of this environmental racism is also a result of political agendas and the lack of ethics in the capitalist, corporate structures that tend to keep their growth as their priority while jeopardizing with the environment. Environmental activists taking up the forefront of policy-making agendas has given some hope against years of racial discourses. Many environmental justice plans have sprung up as a result. It is evident since, “more than $12 million in grants for local community projects serving environmental justice areas, and allocated resources to address health inequities, air quality, and renewable and efficient energy.” (Javorsky,2019) Under Trump’s leadership however, environmental justice movements have seen a major downfall due to the president’s lack of belief in environmental hazards or climate change let alone environmental injustices due to racial discourses. However, according to Bullard neighbourhoods in these cities face environmental racism also because many privileged find these areas as ‘paths of least resistance.’ Due to low number of advocates or lobbyists speaking up against racial prejudices – it gets easier for the white privileged man to exploit them. Bullard claims that “local governments and big businesses take advantage of people who are politically and economically powerless, and set-up shop in places where there is lax enforcement of environmental regulations.” (Bullard, 2000)

It is clear then that the topic of environmental racism is becoming fuzzy by the day and in fact a shortfall of proper strategy has caused institutional barriers to environmental equality/justice. It is only, in this age of technology, now possible to achieve justice through the communities own struggle to keep up and creating networks so as to share information and form an organized opposition against political, historical and even social (racist) jurisdictions.

WORKS CITED

Bullard, Robert D. 2000. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. 3rd Edition. Westview Press.

Checker, M. (2005). Polluted promises: Environmental racism and the search for justice in a southern town. New York: New York University Press.

Bullard, R. D. (1993). Confronting environmental racism: Voices from the grassroots. Boston: South End Press.

Javorsky, N. (2019, May 12). Which cities have concrete strategies for environmental justice? Retrieved from https://grist.org/article/which-cities-have-concrete-strategies-for-environmental-justice/

Environmental Injustice: Is Race or Income a Better Predictor? Social Science Quarterly , December 1998, Vol. 79, No. 4 (December 1998), pp. 766-778

Godsil, R. D. (1991). Remedying Environmental Racism. Michigan Law Review, 90(2), 394. doi:10.2307/1289559

ADDRESSING ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM: Robert Bullard: Journal of International Affairs , Vol. 73, No. 1, CLIMATE DISRUPTION (Fall 2019/Winter 2020), pp. 237-242

Robyn, L. M. (2020). Environmental Racism:. Indigenous Environmental Justice, 92-114. doi:10.2307/j.ctv10qqwrm.9

Pulido, L. (2017). Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California. Environment, 379-407. doi:10.4324/9781315256351-17